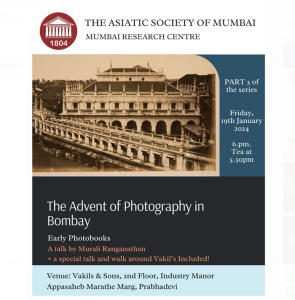

On 19 January, historian Murali Ranganathan delivered the third part in a series sponsored by the Asiatic Society of Mumbai on the advent and early days of photography in Mumbai. The elegant workers’ cafeteria of Vakils Premedia in Prabhadevi was jam-packed for the event by an attentive audience. Ranganathan’s talk was followed by a brief discussion and a comment by Bimal Mehta on the Vakil’s progenitors’ strong association and support of MK Gandhi in his return to India and in the course of the independence movement.

The evening ended with a conversational visit to the exhibition room at Vakils, displaying many of the historical images and documents of the association with Gandhiji as well as several other important photo and art books produced by the company over the years for various national institutions.

Ranganathan has a great feel for the places of Western India and seems to know every street and lane in the city of Mumbai. Knowledgeable in how the city was built and grew, why and how its businessmen created its buildings and institutions and particularly how they synthesized and created its cultural traditions. According to him, Bombay, as it was known until recently, has always been at the forefront of both culture and technology – its citizens, the earliest adopters of new ideas not just in the country, but globally.

Ranganathan has a great feel for the places of Western India and seems to know every street and lane in the city of Mumbai. Knowledgeable in how the city was built and grew, why and how its businessmen created its buildings and institutions and particularly how they synthesized and created its cultural traditions. According to him, Bombay, as it was known until recently, has always been at the forefront of both culture and technology – its citizens, the earliest adopters of new ideas not just in the country, but globally.

Photography came to Bombay soon after its invention as a somewhat industrial process almost simultaneously in Paris in 1839 and in London in 1840. Ranganathan recounted that three Parsi cousins happened to be in London in 1940 where they saw the new invention. The invention came to Bombay in 1844 and with European and Indian practitioners in the city gained traction with the Photographic Society of Bombay formed in 1856. The third such society formed in the world included among its founding members notables of the city’s business community, including traders in photographic chemicals. He went on to recount the advent of the railways and its impetus to both travel and photography in the country resulting in the first travelogues and books with photographs, although the photographic plates of the books were printed in England and then bound along with the text in Bombay.

It’s clear from Murali Ranganathan’s historical detective work and the granularity of his understanding, that there is much to learn about how technology migrates, is adopted and serves the cultural and business needs of the community and even the ups and downs of the economic conditions that color its progress. The printing industry, for whom this work is especially insightful, must support this work meaningfully, expand the collection of the Asiatic Society and help in taking forward the lecture series. In addition, the glass negatives that abound in every historical photography collection but seem to be lacking in our country must be found, purchased and preserved.

An extract from Ranganathan’s Asiatic Society Lecture at Vakils and Sons

“In December 1863, a small band of travelers from Bombay embarked on a long journey which would take them to all the important cities of India. The group was made up of Bombay citizens who had already played a prominent role in the public life of the city. The trip had been initiated by Cursetjee Nusserwanjee Cama (1816–1885), one of the leading businessmen of Bombay who controlled many of the new textile mills that had sprung up in the city in the previous decade. He was said to be worth eighty lakhs of rupees, a stupendous sum of money for the 1860s, and it was expected that he could soon lay claim to the distinction of being a crorepati (Vachha, 606).

“In December 1863, a small band of travelers from Bombay embarked on a long journey which would take them to all the important cities of India. The group was made up of Bombay citizens who had already played a prominent role in the public life of the city. The trip had been initiated by Cursetjee Nusserwanjee Cama (1816–1885), one of the leading businessmen of Bombay who controlled many of the new textile mills that had sprung up in the city in the previous decade. He was said to be worth eighty lakhs of rupees, a stupendous sum of money for the 1860s, and it was expected that he could soon lay claim to the distinction of being a crorepati (Vachha, 606).

Cama had funded many of the social reforms that had been initiated in Bombay in the 1850s including the establishment of schools for girls. The other two Parsi members of the group, Ardeshir Framjee Moos (1827–1895) and Khorshedjee Rustomjee Cama (1831–1909), were relatively younger but had also been active in the public arena. Moos, a teacher at the Elphinstone Institution, was involved with the education of girls and the public library movement in Bombay, especially at the Native General Library. K R Cama had pursued a career in business, but by the early 1860s, had decided to study the ancient Persian languages and the Zoroastrian scriptures.

Dr. Bhau Daji (1821–1874), a Hindu medical doctor, who could then lay claim to being one of most famous citizens of Bombay, provided the intellectual leadership to the group. Belonging to the early batches of students who had benefited from a modern English education, Bhau went on to acquire a medical degree from the Grant Medical College in 1851 and soon became famous for his surgeries which bordered on the miraculous. Bhau was closely associated with the Cama family who financed the charitable dispensaries where he dispensed free medicine to the poor. Bhau had played a prominent role in practically every public forum in Bombay from the early 1850s. He had been the Honorary Secretary of the Bombay Association which, for the first time, made a representation regarding the rights of Indians to the British Crown in 1852. Bhau was also interested in the ancient history of India and had written a few scholarly essays.

The fifth member of the travel party was Edward Rehatsek (1819–1891), a professor of Latin and mathematics at Wilson College. A native of Hungary, Rehatsek had adopted an Indian lifestyle after coming to Bombay in 1847. An accomplished linguist, he was fluent in Arabic, Persian and Hindustani and had been invited by Bhau to join the group to help him in taking notes of their observations and for making sketches of the natural scenery.

The group was accompanied by two Parsis, who managed the practical aspects of the journey: Mancherjee Merwanjee Naliarwalla and his assistant Rustomjee Fakeerjee Cooper. Dr Bhau had also engaged two Hindu personal servants to cook and serve his meals.

At a time when travel for pleasure or leisure was rare among Indians, this eclectic group had considerable experience of traveling. Rehatsek, who had travelled across Europe, studied in America, and settled in India, had easily visited most countries. Both the Camas had stayed in China as young men for two-year stints to learn the ropes of international trade, Cursetjee in the 1830s and Khorshedjee in the 1850s. The junior Cama had, from 1855, also spent three years in England as a business partner in Cama & Co, the first Indian trading firm to operate from that city. He had also engaged in philological studies in continental Europe before returning to India in 1860.

Though the railways, which had proved itself to be a very convenient and fast mode of travel, had been slowly spreading its web across India for nearly a decade by 1863, most parts of the country were still not part of the rail network. The group took the train wherever they could but also had to travel by road in bullock carts. Leaving Bombay on December 22, 1863, the group traveled by train up to Solapur, with a break in Pune. From Solapur, they took a circuitous land route to Hyderabad where they spent a few days. They then headed towards Madras, yet another colonial city which they could compare and contrast with Bombay.

The travel party boarded a steamship from Madras to Calcutta after a stay of 10 days. Though the sea journey lasted only five days, they found it very uncomfortable. The experience of boarding the steamship mid-sea during a storm at Madras had unnerved them and the group suffered from seasickness for most of the voyage. They were relieved when they reached the mouth of the Hooghly River and looked forward to reaching Calcutta. After spending two weeks in the city, they set off on a journey across North India visiting all the major cities including Benaras, Lucknow, Agra, Mathura and Delhi.

Though they had intended to go on to Kashmir, Lahore and return via Karachi, they were overtaken by the harsh Indian summer and decided to turn back to Bombay. Traveling through the Maratha-ruled states of Gwalior and Indore by road, they boarded the train for Bombay at Jalgaon. The entire journey took them over four months to accomplish.

The group traveled in a style befitting their privileged status. There were Parsis resident in all the cities they visited who had made arrangements for their stay and travel at most places. Armed with letters of introduction to high officials across India, they expected to be treated like a diplomatic delegation. They were cordially received everywhere they went except for a rare instance or two. In all the princely states they visited, they had an audience with the rulers, including the Nizam of Hyderabad and the Raja of Benaras.

By the early 1860s, photographic studios were beginning to mushroom in both Calcutta and Bombay. On the eve of their departure from Bombay, the group had posed for photographs at the studios of Hurrychund Chintamon. When they spotted a studio in Calcutta, they stepped in for yet another group photograph which was reproduced in the book.

The primary objective of the trip for the group was to document and disseminate their experiences and impressions once they returned to Bombay. Ardeshir Framjee Moos seems to have maintained a travel diary while Bhau Daji would have kept notes on the antiquities and monuments they had seen on their journey. Edward Rehatsek may have sketched the important landmarks and scenes they saw on the journey. Besides they made a large collection of photographs which could be used to illustrate their lectures and publications.

The travelogue as a literary genre was just then emerging in Gujarati. Though travelogues in the modern style had been written in Gujarati since the 1830s, the genre had still not caught the public imagination. However, the publication of Dosabhai Framjee Karaka’s Great Britain katheni musafari [Travels in Great Britain] in 1861 seems to have made a big impact. Published in a quarto edition with full-page illustrations and printed in an attractive easy-to-read font, it proved to be very popular.

After returning to Bombay in April 1863, Moos seems to have undertaken the task of writing a travelogue on behalf of the entire group. The text of the travelogue was ready by early 1864. It was intended to be a sumptuous publication reflecting not only the status of the travelers but also the importance of the trip. It would be profusely illustrated in color. The photographs that had been collected were sent to London in 1864 to be chromolithographed as the technology and expertise were not available in Bombay. However, because of inordinate delays at the printing firm they had contracted with, the proofs of the lithographs arrived in Bombay only by 1866.

But in 1866, an upheaval took place in Bombay which derailed all plans for publication of the travelogue. From 1860, Bombay had been enjoying a period of extraordinary economic boom on the back of very high prices for exported cotton in the United Kingdom due to the American Civil War which had cut off supplies of American cotton. This boom had led to a high degree of speculation in all commercial ventures and the share market was in a tizzy. When news of the termination of the Civil War reached Bombay, cotton prices crashed overnight and the entire economic edifice of the city collapsed.

Many of the leading citizens of Bombay filed for bankruptcy and faced financial ruin. The two prominent members of the group, Cursetjee Nusserwanjee Cama and Bhau Daji, were severely affected by this bust and lost all their assets. Not only did the book lose out on their backing, there was little likelihood that there were buyers who would be able to afford its high price.

The project remained in abeyance for nearly five years but Moos continued to hope that his work would be eventually published. The visit of Prince Albert, Duke of Edinburgh, to India in 1870 provided him with just that opportunity. As associating a book with an important personage was an assurance of its success, both financially and otherwise, Moos dedicated the book to the Prince with his permission.

The first volume of the travelogue, Hindustanma Musafari, was finally published in August 1871 after a delay of seven years. It covered the journey until the departure from Calcutta. While the book was printed in Bombay at the Education Society’s Press, the map and the sixty full-page color illustrations were lithographed by the famous London firm of Vincent Brooks, Day & Son. The full-cloth binding had gilt lettering and design. Moos also included an English translation of a few stray passages from the Gujarati travelogue. The second volume was never published.”