Just over a week ago, on 29 June, Landa Digital Printing, which is the trading name for Landa Corporation, filed a request for a stay of proceedings to formulate a debt settlement. The court granted a 14-day freeze to give potential buyers the time to assess the company and see what can be salvaged.

The immediate problem relates to cashflow, with the current investors refusing to put any more money into the company. That left Landa unable to service its debts and pay its bills. But to understand how this has come about, and what the outcome is likely to be, we really have to look back at the history of the company.

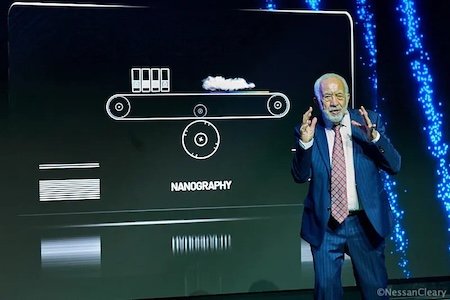

The Landa presses originally burst onto the scene to great fanfare at Drupa 2012, with packed presentations in a purpose built theatre and Benny Landa himself introducing the presses and the nanographic process behind them. In some ways, the Nanographic concept behind these presses grew out of Benny Landa’s first success in developing the Indigo liquid toner presses. He sold Indigo to HP for around $850 million and used the money to set up Landa Labs to explore new technologies. The Nanograpic process was an offshoot of one of those.

As with Indigo, the process take the offset approach of first printing the image to an intermediate media and then transferring it to the final substrate. In this case, the water-based inks are jetted onto a moving blanket that is heated. This heat helps to evaporate most of the water content out of the ink, leaving behind the dots of coloured pigments. The belt then moves the dots on to the substrate, which is not heated. The sudden change in temperature causes the dots to bond with the cooler substrate, pulling them off the belt.

The ink dots sit on top of the media, forming a very thin film said to be just 500 nanometres thick, which is claimed to be half the thickness of an offset image. This film is so thin that the image will take on the surface finish of the substrate, be that gloss or matte. This also results in a very sharply defined dot, with no gain, regardless of the substrate. It works on a wide range of media, including paper and paper-based boards as well as plastics and films, without any need for pre-coating. The inks are said to be instantly dry as they come off the press, ready for further finishing.

Photo- Nessan Cleary

The main advantage of this approach is that it takes the water out of the ink before it reaches the substrate. The disadvantage is that there’s no room for any problems with the transfer belt. The belt has to hold the drops of ink in place until they are transferred to the substrate, and all the ink has to be transferred or else it will contaminate the next image. Originally Landa claimed that this process was so efficient that there wasn’t even a cleaning system for this belt. It quickly became obvious that this belt was the weak point in the system and that it would need to be treated as a consumable with the inevitable struggle to manage the cost of this. These issues led Landa to reach out to the chemical group Altana for technical help, with Altana ultimately investing in equity in the company.

For that first outing back at Drupa 2012, Landa showed six presses, three sheetfed and three webfed, in a range of sizes, with the first said to be available in the second half of 2013. The three webfed models included the 560mm-wide W5 for packaging; the 1020mm-wide W10, also for packaging, and the 560mm-wide W50 for high volume double-sided printing to paper. My original report from the show noted that the sheetfed presses could run up to eight inks and included: the S5, a simplex B3 press; the S7, a B2 model for single or double-sided printing; and the S10 B1 press, the only one to finally make it to market. At that time, Landa quoted a speed of 13,000 sph, which was wildly unrealistic. For comparison, Landa is quoting 6,500 sph for the latest S11 models released in 2024, or 11,200 sph with an additional high speed module.

This neatly illustrates a major issue of credibility. Every company exaggerates its potential – that’s the nature of marketing – and countering that marketing helps to keep journalists gainfully employed. But Landa took this to another level altogether. The nano-sized ink particles that Landa claimed as a breakthrough are not very different to the nano-sized particles that some other ink manufacturers, including Kodak also use. The mysterious ink ejectors were just the standard printheads available to all manufacturers. The models shown in 2012 used Kyocera heads but every Landa press since then has used Dimatix Samba heads. These things, together with the wildly exaggerated speeds and overly optimistic delivery dates all helped to muddy the waters and obscure just how much further development the technology needed. That ongoing development meant that Landa was constantly chasing funding.

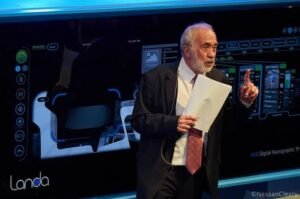

Photo- Nessan Cleary

Back at Drupa 2012 there was much talk of customers signing letters of intent, with £10,000 deposits to book their place in the queue for the new technology, and of partnerships with other press vendors. But Landa was well aware that it had taken HP many years and at least a further $1 billion dollars to turn his Indigo technology into a profitable business. I remember Bernard Schreier, then the CEO of Heidelberg, telling me and other journalists that he believed all the effort was aimed at persuading him to commit Heidelberg to fund the further development that Nanography would need. Heidelberg and other press manufacturers did look at the technology but opted to pass on it.

Instead Landa set up its own factory in Israel and concentrated on developing the sheetfed B1 model, the S10/ S10P, saying that this had proved the most popular. The next couple of years brought announcements suggesting a commercial launch around Drupa 2016. Yet it was obvious from the print samples shown at that year’s Drupa that Landa was still some way off perfecting the technology. That didn’t stop Landa from taking orders for those presses though it was 2017 before the first beta sites were announced.

The first commercial installations only started in 2022. By all accounts, the customers are happy with the results, with several, such as the Bluetree Group in Britain, having installed a second press. Certainly the last set of print samples that I saw, at last year’s Drupa, were excellent, including an impressive range of different applications printed on the webfed W11 that is still in development.

Photo- Nessan Cleary

A very quick look at all the installations listed on Landa’s News page, which does not include all the actual installations, suggests that about a third of the presses have gone to Europe and two-thirds to North America, plus at least four to China. Of these, the S10P/S11P perfecting model for publishing appears to be roughly twice as popular as the simplex packaging version.

These are premium presses, with a price tag of around $3.5 million, which can easily balloon to $5 million for a complete installation. Naturally, this kind of capital investment is paid in instalments, meaning that it takes time for Landa to make a profit on each press. That’s a huge problem for a company that has yet to reach commercial profitability and relies on the ongoing sales to complete its development.

In that context, Drupa 2024 does appear to have been a turning point for Landa, but not in a good way. Far from being the “phenomenal event” that far exceeded sales targets as CEO Gil Oron claimed, Landa only managed to sell a further 11 presses, less than the 16 presses the company is said to have been hoping to sell. Up until the end of last year, Landa was claiming to have installed 70 presses but it’s become clear in the last week from the court filings that the true number is 50 installations.

Photo- Nessan Cleary

That’s a significant number but not enough to carry the weight of all the development costs behind Nanography. Instead those 50 presses represent a handful of applications that justified the cost of those presses. The crux of the problem for Landa is that there is still a limited market for B1 inkjet presses, given that offset is considerably more cost-effective for most applications other than those involving variable data.

Benny Landa himself told journalists in 2012, “To be mainstream, it must be competitive with offset with the same cost and speed as well as the ability to print on any kind of paper stock.” That assessment still holds good, and may also explain why Landa gave up on the B3 and B2 models that he had shown back in 2012 as those markets are far more price-sensitive. Indeed, it was clear from the last Drupa that B3 inkjet is now cost effective against offset.

Nanography, as with any inkjet technology, has proven costly to develop. In 2018, shortly after the first beta installations, Landa required a further round of funding to continue developing its technology. That led to a $300 million investment, mainly from Altana, but in the form of a secured loan rather than equity.

In 2021, Landa sought to merge with a Special Purpose Acquisition Company or SPAC on the Nasdaq stock exchange. A SPAC is essentially a shell company that can be used to raise funds for an acquisition. So merging with a SPAC would have achieved a listing on the Nasdaq and access to a lot more funding. In this case, Landa is said to have targeted a $2 billion valuation, which seems like a rather bold figure given that it was 20 times the company’s annual revenue at that time, said to be around $50 million. More to the point, Landa Digital Printing has never actually made a profit.

So this is the background to Landa’s current troubles. In the second half of this story I’ll go through those troubles and the likely outcome.

First published on 7th July 2025 in the Printing and Manufacturing Journal. Republished by permission.