Heidelberg has announced a radical restructuring plan, which is aimed at clearing its debts but also essentially rethinks its approach to digital printing of packaging. The major part of this restructuring is to concentrate on those products with the highest profit margins and to give up on those that don’t earn enough to justify their place in the portfolio. Consequently, Heidelberg is abandoning its Primefire 106 B1 inkjet press, saying that the market for digitally-printed packaging has grown more slowly than anticipated. In practice this means that the production has stopped and the R&D has been frozen while Heidelberg searches for external investors to support further development.

It’s inconceivable that Heidelberg did not first approach Fujifilm to ask it to put more money into the Primefire, which indicates that Fujifilm turned it down. Interestingly, when I asked Heidelberg whether or not it would continue to work with Fujifilm or look for another inkjet partner, the company replied, “At this stage it is too early to make a statement.”

That said, both Heidelberg and Gallus have said that the Labelfire, Gallus’ narrow web hybrid press that also uses Fujifilm printheads and ink, will continue.

Heidelberg says that it is still working out who’s going to service the existing Primefires, but that “customers do not need to worry about servicing the machines already in the field.” I think that if I was trying to keep a large B1 inkjet press going then I would be quite concerned that the company that supplied it had not thought about the servicing before this announcement. Heidelberg is also still to decide whether or not to continue developing its Web-to-Pack software, though I think that this was probably one of the smartest parts of its digital packaging program.

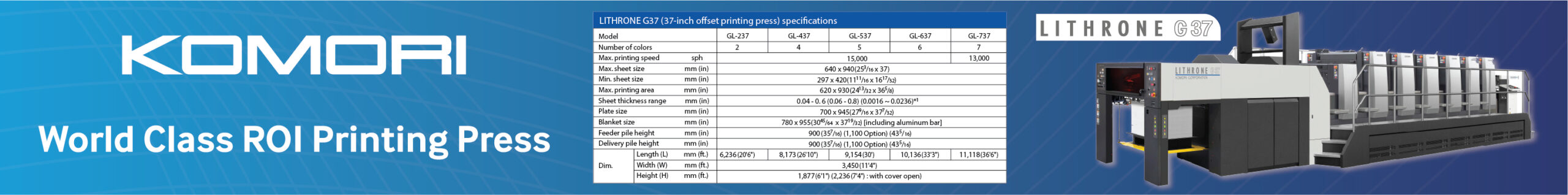

The really interesting aspect is that Heidelberg seems to suggest that developments to its offset presses have rendered a digital press less attractive to the packaging market, even for relatively short runs, given that the sort of run lengths in packaging that would justify a B1 press tend to be longer than other market sectors. The argument is that the combination of quick makereadies with fast printing speeds means that the press can produce a large number of small to medium runs in any given shift. This means that digital presses only really score on very short runs of just a few hundred impressions, which are not so common in the packaging market.

The other advantage that a digital press has – little to no makeready time – is cancelled out by the faster running speed of the offset press, up to 18000 sheets per hour, which none of the current inkjets can match. It follows that if you’re going to use an offset press for short-ish run lengths then you really have to have a very efficient workflow, able to gang jobs together on the same plates, and to queue jobs to optimise the paper loading and any further finishing steps – but any competent printer ought to be able to manage this, and there are plenty of vendors and consultants, not to mention magazine articles, able to advise on optimising workflows. Needless to say, I’ll take a closer look at this digital versus offset argument as well as the new presses that would have been shown at Drupa this year in a later story.

The big questions

The bigger question that Heidelberg has yet to answer is, how will it approach inkjet printing, given that these presses are becoming more widespread? Heidelberg told me that it still sees a future in inkjet printing, yet it has just abandoned its foothold in this technology. I think it’s likely that Heidelberg’s plans revolve around rebadging another vendor’s inkjet presses, as it has successfully done with dry toner presses, offering several Ricoh models complete with a Heidelberg workflow.

Heidelberg’s sheetfed VLF presses, the Speedmaster XL 145 and 162 are also for the chop. The main problem here is that this is a relatively small but stable market, where there’s limited opportunity to sell new presses and customers don’t tend to be in a hurry to replace those they already have. So Heidelberg is currently talking with customers to see if any of them want to place a final order before production stops altogether. Heidelberg has said that it will meet all legal and contractual obligations in terms of spare parts and servicing.

For now, future investment spending will focus on developing integrated system solutions that span machines, software, consumer goods and performance services. Heidelberg states that it’s vision is to “create a cross-industry IoT-based platform to automate all customer-supplier relationships. This solution will enable print shops to secure a significant gain in productivity.”

Essentially, digitisation for Heidelberg appears to mean using IoT to make offset presses more attractive, rather than digital presses, and presumably rebadging other vendor’s digital presses to fill in the gaps. The trick, of course, will be persuading customers that Heidelberg has the necessary software expertise to do this. This will be harder than it sounds since most other vendors are planning on doing the opposite – using their IoT skills to give digital devices an edge over conventional presses. Heidelberg may have hoped that its subscription business model gave it an edge here, but the subscription model too has been given the chop according to the Heidelberg action (restructuring) plan of 18 March 2020.

Rainer Hundsdörfer, Heidelberg’s Chief Executive Officer, explained, “Heidelberg’s realignment is a radical step for our company that also involves some painful changes. As hard as it was for us to make this decision, it is necessary in order to put our company back on track for success. Discontinuing unprofitable products enables us to focus on our strong, profitable core. This is where we will further extend Heidelberg’s leading market position by leveraging the opportunities of digitalization. Going forward, we will continue to provide our customers worldwide with technologically leading digital solutions and services across the board.”

The other half of this restructuring plan involves a large cash injection of roughly €375 million in the form of a return transfer of part of the liquidity reserves from the trust fund managed by Heidelberg Pension-Trust e.V. Heidelberg says that this will not affect the existing and future pension entitlements as the Board of Heidelberg Pension-Trust has agreed to reduce the assets held in trust to a level that provides for those pension entitlements not covered by the statutory pension plan.

This, along with the repurchase of a €150 million high-yield bond should reduce the company’s outstanding debts, giving it a degree of financial stability. Ultimately the aim is to achieve a €100 million improvement in EBITDA, excluding the restructuring result, with Heidelberg stating, “The financial independence that this will create will give us greater room for manoeuvre and make the company more responsive.”

The restructuring will also affect up to 2,000 jobs worldwide. This may also include plant closures, though Heidelberg has yet to negotiate with its employee’s representatives. Depending on the outcome of those negotiations as well as accounting charges in the financial year 2019/2020, the non-recurring expenses necessary to implement the action package are estimated to total about €300 million.

Heidelberg has stressed that this is part of a long term business plan and not something caused by the current global crisis over the Coronavirus. Nonetheless, the pandemic will affect Heidelberg’s earnings, with the company warning that the full year results will probably show a loss. The restructuring itself will mostly affect the coming year so that Heidelberg is not expecting to see a return to profit until at least the results from its 2021-2022 financial year.

However, it’s also worth noting that Heidelberg has lost several board members recently with Ulrich Hermann officially stepping down this week. Hermann oversaw the subscription business model that Heidelberg is now so heavily reliant on and his departure leaves just two board members – CEO Rainer Hundsdörfer and CFO Marcus Wassenberg.

Instead, Heidelberg has set up an Executive Committee, which sits one level below the management board, and is responsible for cross-product customer solutions and the operational functions. Hundsdörfer says that this will be more efficient but then every leader, whether of companies or countries, thinks that they would be more efficient if they were just left to get on with making decisions without anyone else questioning them, which is fine, right up till the point when it isn’t.

Personally, I think it’s a little strange that a company the size of Heidelberg is ultimately run by just two board members. I suspect that most shareholders would probably feel more reassured if the Executive Committee were promoted to full board members and truly able to exercise some kind of oversight, which is after all one of the major functions of a board of directors. I doubt that I’m the only person that feels more than a little uneasy over this lack of accountability.

Such oversight is especially important right now, when Heidelberg is completely altering its business model, relying more heavily on subscriptions, servicing and data analytics, having outsourced most of its postpress range and now cutting its heavy metal product portfolio back to the core, most profitable presses. And let’s not forget, the Primefire was once a big part of Heidelberg’s future and now that’s just seen as eight years and quite a bit of money spent on chasing the wrong direction.

The article was first published on nessancleary.com