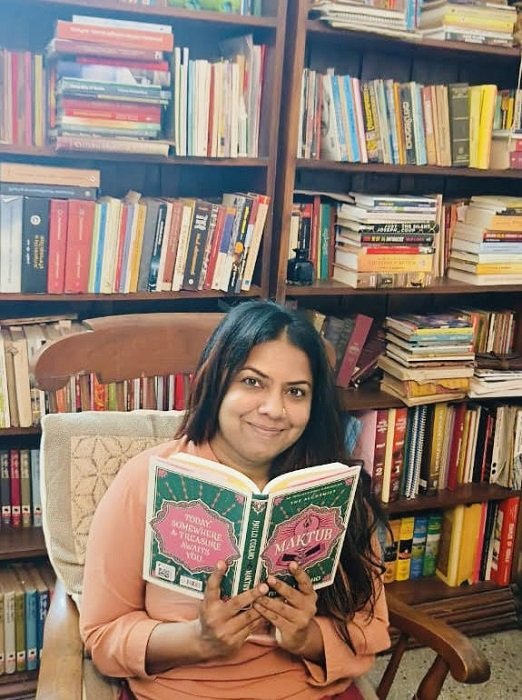

Correspondent Priyanka Tanwar had a chat with Malayalam translator Kabani C to know about her journey into the world of translations, the state of Malayalam translations, how to keep the author’s style and terminology consistent, incorporating author feedback in translated works, adding a localized feel, challenges in the field and much more.

Edited excerpts:

Indian Printer & Publisher (IPP) – How long have you been a translator? How did you become a translator?

Kabani C – I am a reader and literature enthusiast. My friends of a rather lonely childhood were books and stories I heard and imagined. My translations and the writing I do is a by-product of my passion for reading.

As a teenager, I was impressed by the Jnanpith speech of Mahasweta Devi. What a powerful oratory! What a powerful woman! I translated that English speech into Malayalam. That was my first published translation. As it was appreciated well, I started translating, mostly random articles. It was the amateur phase of my translation career. It was not done for any specific purpose or to be published. This phase gave me information and familiarized me with translation chemistry. This made me translate many plays, including the Sword of Tipu Sultan by Girish Karnad.

The professional phase of my translation started after I received my master’s degree. It was an even lonelier period of my personal life after my mother’s untimely and extremely shattering demise. I dug more into books and entered the extremely creative world of serious translation with the novel To Know a Woman by Amoz Oz. Since then, I have translated almost 45 books in all genres – fiction and nonfiction, literature and popular fiction by authors, including Amoz Oz, Salman Rushdie, Perumal Murugan, Harsh Mander, Mahasweta Devi, Paulo Coelho, Preeti Shenoy and Shobha De into Malayalam.

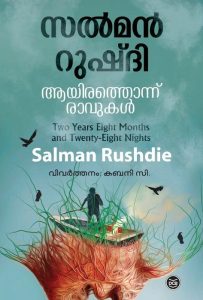

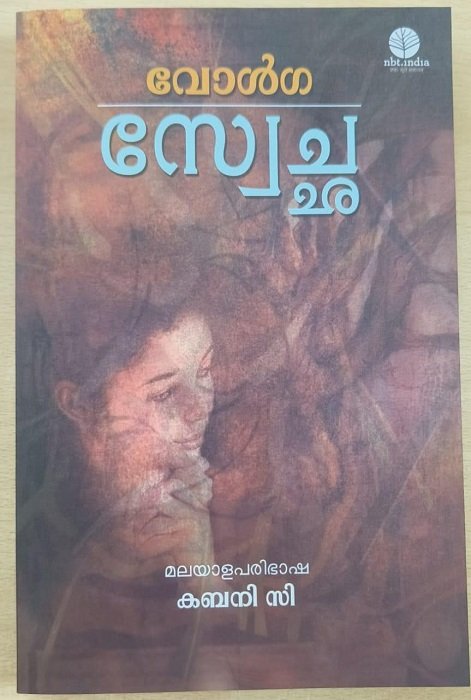

My important translations are Daughter of the East by Benazir Bhutto, Unbowed: A Memoir by Wangaari Maathai, Letters from Burma by Aung San Suu Kyi, Keezhalan by Perumal Murugan, Two Years Eight Months Twenty-Eight Nights by Salman Rushdie and Swetcha by Volga. I have translated three books by Paulo Coelho into Malayalam; two of them were translated into Malayalam before the English versions were out. I translated Nazim Hikmet’s autobiographical novel, Life’s Good, Brother with the Turkish Consulate’s grant. I translated Ek- Kori’s Dream by Mahasweta Devi, Swetcha by Volga for National Book Trust, India, and Amish Tripathi’s two novels in his Ramachandra series for Westland. I have edited several books as well.

I am a governing board member of Samatha, a collective for gender justice, and actively involved in publishing original and translations of books related to women’s struggle.

IPP – How do you ensure the quality of the translated work? How do you keep the author’s style and terminology consistent?

Kabani C – I think the text has to be read from a reader’s viewpoint. Otherwise, we could deviate from the nuances of the text. The next readings can be through the eyes of a translator, in which we try to grasp the soul of the text.

A translator does a minute, subtle, intimate reading of the text and its layers, and subtexts. I try to understand the author through the oeuvre, which will enhance my knowledge about the literary environment and repeated milieu of the fictional world. I keep a tab on and note separately the specific terminology and style used by the author. A translator has no moral authority to change the author’s style, which should be kept intact as far as possible.

IPP – How do you incorporate author feedback in your translated works?

Kabani C – I have built close connections with many authors whose works I have translated. I translated Preeti Shenoy’s One Hundred Little Flames into Malayalam and received positive reviews. Her mother, who can read both English and Malayalam, said it was the best translation of Preeti’s work. I interacted with Chetan Bhagat when I translated his Girl in Room No 105 and An Arranged Murder. The Malayalam title of Girl in Room No 105 was finalized after discussing it with him in person. I had conversations with Shobha De, Perumal Murugan, and Amish Tripathi on their works I translated and on their literary world.

But my most fruitful interaction had been the one with Volga, the famous Telugu writer. I translated her much-celebrated Swetcha into Malayalam, which was published by the National Book Trust. It is a novel move around Aruna, a young lady who walks out of the family for ultimate freedom. It created an uproar in the Telugu literary and social circles in the 1980s. Impressed by her masterpiece, I went to Secunderabad to chat with her. I talked to her the entire day about Swetcha and her life. Apart from getting the soul of the text intact, including minute details such as the proper pronunciation of the retained Telugu words, she influenced me a lot.

IPP – Do you add a localized feel to your translations? If yes, what strategies do you employ to achieve this end?

Kabani C – Yes. When Keezhalan, a Tamil novel, was translated into English, the Tamil words such as the names of the months were completely changed to gain a pan-India audience. But Malayalis are culturally and geographically very close to Tamil Nadu. So, I retained as many Tamil words as I could, after going through the Tamil version. The same thing happened in the case of Swetcha. We even rearranged the chapter divisions after considering the author, the editor, and the Telugu version.

When I was doing Chetan Bhagat’s novels, it was quintessential to retain the urban dictionary as his milieu is the middle-class Delhi urban youth. When I did the same with Preeti Shenoy’s One Hundred Little Flames, in a review, The Indian Express wrote – “when the cover song is as good as the original.” I translated three novels by Shobha De and received recognition for retaining the Mumbai upper-class flavor.

IPP – What challenges do you face while translating vernacular Indian literature?

Kabani C – When I translate into Malayalam, there are many challenges. One is to get the vocabulary intact – simultaneously apt and not flowery, not Sanskrit-laden. The translation should go with the flow of the mother tongue but shouldn’t lose the exotic texture either. In this regard, Malayalam is ill-equipped in many ways as a language. We consider words that are almost Sanskrit as literary language. We don’t have, for example, a separate single Malayalam word for grandparents and we won’t use ‘she’ for an elderly one or for whom we have respect and so on. Our urban idioms are not so well-established. Malayalam is in a state of continuous evolution as far as translation from another language is concerned.

IPP – What role do literary agents and agencies play in the promotion of translated works?

Kabani C – In Malayalam publishing, there are no literary agents and agencies as such. The publishing houses themselves promote the translated works.

IPP – And what about literary festivals and book exhibitions?

Kabani C – The literary festivals and book exhibitions have gone up in number and volume in Kerala in the last five years. Some of the most prominent are the Kerala Literature Festival organized by DC Books, the Kerala Legislature International Book Festival, and the International Festival of Kerala organized by Kerala Sahitya Akademi. Literature festivals are places where we can watch the nuances of the publishing industry where all the three pillars of publishing meet – the writers, the readers, and the publishers. Book-making and publishing is one of the noblest professions in the world. And in these festivals, book rights get transferred. Naturally, they help in the promotion of translated Indian literature.

IPP – Malayalam translations are steadily gaining prominence in India’s translation scene. What are your thoughts on these language translations?

Kabani C – Malayalam fiction has continuously had the best output in the last 50 years. This is one of the reasons for the prominence of translations from Malayalam. There is a new generation of readers who want to read Malayalam novels in English – the expatriates. There is a new wave of good translators. International publishers need new experiences and new areas. Earlier, it was African and Latin American literature. Now, it is the turn of India with Malayalam in the prime slot.

IPP – What is the future of vernacular Indian translations in a global scenario?

Kabani C – There is a bright future for Indian languages, especially Malayalam translations. The world is looking forward to new experiences. Both Bengali and Malayalam have good writers and translators. Nowadays writers are catering to the international market. We have 2.5 million Malayalis working abroad and another section studying outside. This itself is a big market for translation.

Earlier, a Malayalam novel could be read by a non-Malayali only with the help of footnotes. That era of footnote translation is almost over. Translations are no longer addressed exclusively to the non-Malayali readers. We have a global life and naturally, the writing is no more local. Our translators are equipped with contemporary English. Many of them live abroad, many have English as their first language. All these factors contribute to the growth of translation from Malayalam.

IPP – What are the barriers prohibiting the internationalization of regional Indian literature?

Kabani C – Actually, there are no barriers at all. English literature is read the world over as they ruled the entire world, culturally and politically. In the post-colonial era, we gradually asserted our space in the international market. Now many Indian words are understood by the world without footnotes. As we move forward and assert more, the reach will increase.

IPP – What are some commonly encountered perceptions of literature translated into Malayalam among the global reading audience?

Kabani C – Malayalam has a long history of translation from other languages, from every language and every part of the world. It seems to be the most receptive Indian language in this regard. But most other Indian languages such as Punjabi, Telugu, and Odiya need institutionalized efforts to improve the translation publishing ecosystem. So, efforts should be made to get more translations from other South Indian languages into Malayalam and other languages.

IPP – What measures can improve the translation publishing ecosystem in India?

Kabani C – Malayalam as a language of translation will survive without any help. However, many indigenous Indian languages will not survive without institutional support. The government and other cultural institutions dedicated to the cause should take active measures to get minor Indian language works translated. This is a very significant cultural activity, which won’t be expensive. There is a National Translation Mission and a Central Institute of Indian Languages in Mysore. However, most of the activities are concentrated on translating manuscripts and textbooks.

I would add one more point here. A painful racism exists in the translation world! If you are translating into English, you are considered a celebrity and you are paid more, and international prizes are waiting for you. Leela Sarkar, who recently celebrated her 90th birthday, has given her entire life to translating literature from Bengali to Malayalam. Her translations have a more profound influence on Kerala society than any other translation into English. But her work is not celebrity material. She received the Sahitya Akademi Translation Puraskar. And there it ends. I am sure she never made any money out of her work. She translated Rabindranath Tagore, Mahasweta Devi, Sunil Gangopadhyay, Ashapurna Devi, and other Bengali writers simply out of her passion for Bengali literature. And she was pleading with the publishers to accept her work. This needs to be changed. Translations among Indian languages are to be better recognized and remunerated.

IPP – UNESCO has recently declared 2022-2032 as the international decade of indigenous languages. What are your thoughts on this initiative?

Kabani C – Indigenous languages face a serious threat all over the world. Though officially there are 122 languages, the People’s Linguistic Survey of India conducted in 2014 has identified 780 languages of which 50 have become extinct in the past five decades.

Malayalam will be spoken and read mainly as a medium of communication. But I am not very sure about its survival as a creative language. Malayali children are effectively not learning Malayalam in schools. We have English medium schools in the state, which include Malayalam as a second language. English is the medium of instruction in most government and aided schools. Naturally, the children won’t go through the rich literary heritage of the Malayalam language. The generation next doesn’t get an organic connection with the spirit of Malayalam literature. If efforts are not being made, Malayalam won’t survive as a language of literature.